Human Writes: The Birds and the Trees - My Artificial Intelligence Story

Hanging Out With ChatGPT| Assisted-Fiction | Fresh Soup

How do you say ‘short and sweet’ in French?

True story: a few days ago, my French translator, Rosie Pinhas-Delpuech, sent me a review of the French edition of my new book, Autocorrect, from that morning’s Le Monde. It was a slightly blurry image, and my French is so bad that other than the occasional word, I understood none of it. Shira, my wife, asked her loyal servant of the past few months, ChatGPT, for a translation. The helpful bot politely enquired whether she would like a few key quotes or the entire review. My proud wife naturally asked GPT to translate the whole thing, which it did in seconds flat.

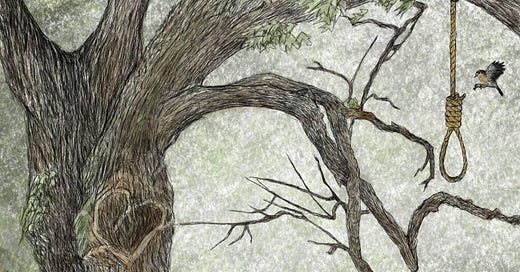

It was a good review, and the translation was excellent, maintaining a poetic cadence that was clearly present in the original French. Just as I was marvelling at my wife’s talented butler, I read the following paragraph: “The first story in Keret’s collection (Correction Automatique) is short and sweet: it portrays a man committing suicide by hanging himself from a tree branch. The tree, dissatisfied with its role, tries to break loose from the rope.”

That really is a sweet story. But it doesn’t appear in the book, nor have I ever written it. When Shira prodded ChatGPT to verify the information, it replied that such a story does not actually exist and that she had misunderstood its previous response.

The AI-invented tale of a man who wants to hang himself from a branch, much to the tree’s chagrin, might not be the first story in my new book, but it is an apt metaphor: technology stands beside us, like a tree that constantly grows, and we – humanity – may choose to either use the tree and enjoy its fruits, or hang ourselves from its branches. Guess which option most of us choose?

With Friends Like These

I have a good friend who always sounds very authoritative. He’s highly educated and sharp-witted, and likes to deliver succinct assertions in a self-assured baritone. After the October 7th attacks, this friend informed me that at least 3,000 Israeli citizens would be killed in the first few weeks of the war, by missiles launched from Lebanon. He has an extensive background in maths and physics, and his explanations were persuasive, detailed and, in retrospect, utterly wrong. I’ve since listened to many more of his confidently-issued facts. Most of the time, he makes sense, yet I can’t forget how assertively he pronounced that half of Tel Aviv was about to be razed, and so I take his truisms and forecasts with a grain of salt.

Increasingly, ChatGPT reminds me of this friend: they’re both brilliant and almost always right, and when they make a mistake, they do so without the slightest trace of doubt or hesitation. The thing is, everyone who knows this man, including myself, has learned to be a little circumspect about his pronouncements. But when it comes to ChatGPT, we’re a lot slower on the uptake.

Vagueness is for Weaklings

Imagine a different AI model, one that speaks confidently on things it’s confident about, but never hesitates to hesitate. One that warns us, for instance, that a certain passage will be difficult for it to translate because of the poor-quality image. Would humanity prefer this somewhat-tentative AI to the unremittingly authoritative kind we have now?

I think the answer is clear. If we really yearned for an AI that is unafraid to admit when it doesn’t know something, it would probably already exist. Uncertainty is not sexy. Deep down inside, we long for an omniscient intelligence that claims it can solve all our problems. An entity that will share its fruits, shelter us in its shade, and offer us a strong branch when we need one—the kind that can bear our weight.

Oh, and just to avoid making a liar out of my wife’s sidekick, I wrote the story:

Chronicle of a Tree