Sisyphus

Out with the old | Fiction | Defrosted Soup

In honor of Groundhog Day, I’d like to share with you one of the first stories I ever wrote, which has only just been translated into English (thanks, Jessica!). I wrote it during my first week of college. I was taking a class on the history of the novel, taught by a well-known and brilliant literary scholar named Meir Sternberg. In one of his lectures, he explained that while a literary description can be circular, repeating itself without developing at all (“the waves lapped at the pier again and again”), a story, by definition, must be linear: it cannot end at the point where it began. I tried to challenge this observation. It was the first time I’d spoken in class, and I was nervous and stammering. Professor Sternberg cut me off mid-sentence, walked towards me in a slightly menacing way, and said, “If you think I’m wrong, then instead of arguing, just show me a story that does that. A story that ends exactly where it started.” And so, after class, I found somewhere to sit in the library and started mentally scanning all the stories I’d ever read, desperately searching for one that would disprove the professor’s thesis. After two frustrating hours, unable to remember even a single story that fit the bill, I decided to write one myself.

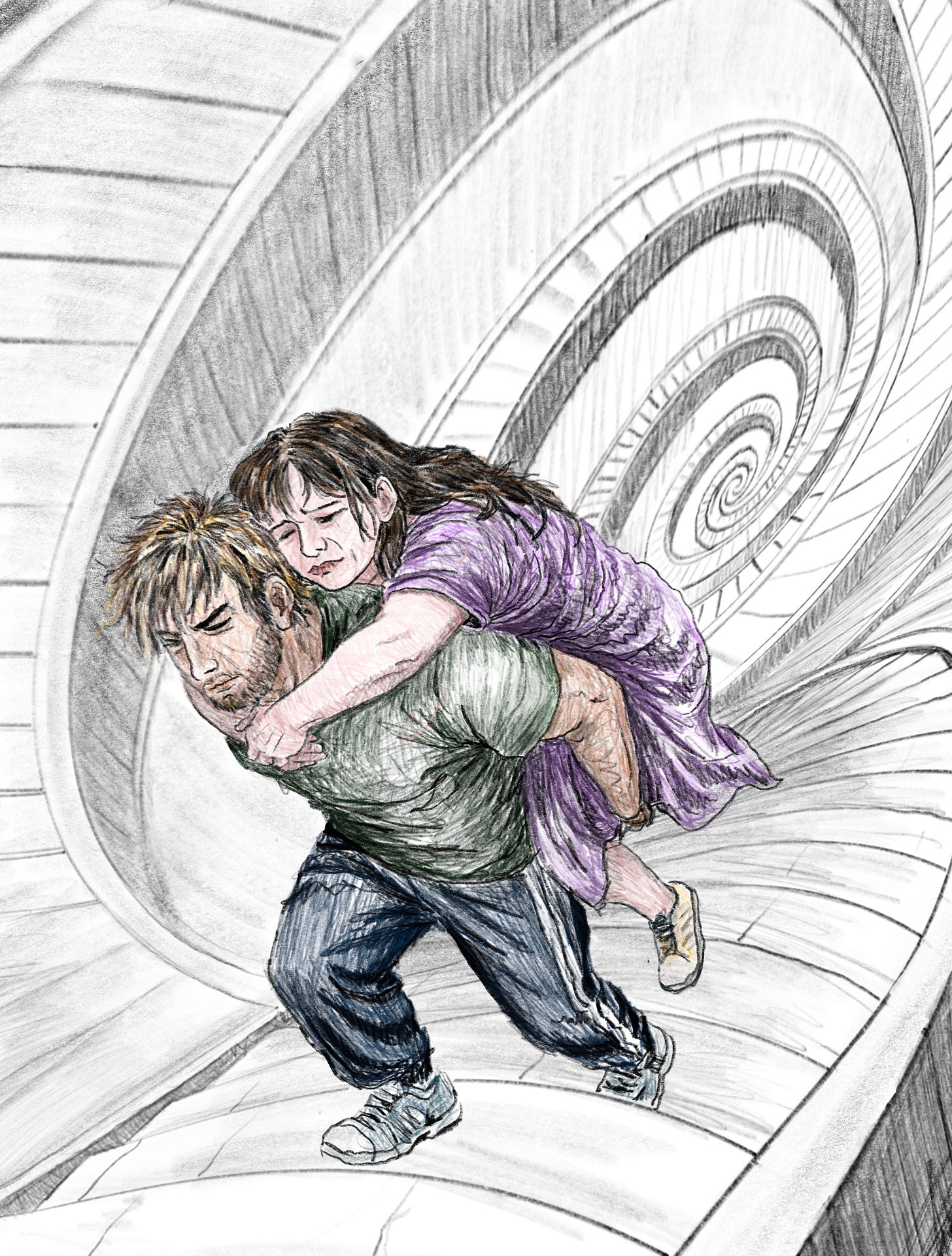

Every week, same thing. Four fifteen on a Friday, I’m in my gym clothes, Yakov’ll be here any minute to pick me up, and she has to say: “Maybe you could skip it today? You know how much it hurts Dad’s feelings when you don’t stay for kiddush.” And every time I have to explain to her all over again how I work overtime like a dog to pay for her dad’s old-age home, and how Friday afternoons are the only chance I get to see my friends, play a little soccer, forget about my troubles for a while. And every week all over again she has to say: “Dad wants to know if I’m a widow ‘cause my husband’s never at the dinner table.” And I always say she can tell her meddling old man that, yeah, she is a widow, and if he wants his daughter’s husband to come back to life, maybe he should stop sucking up all our gelt for that five-star home and move into one that doesn’t break the bank. And that bitch always has to say: “Believe me, Moshe, with a husband like you, I’d be better off widowed.” That pisses me off every time, and I slam the door behind me, and then I spend the whole match thinking about everything—the argument, and her, and how it’s bad enough I have to eat shit at work but now I have to eat it at home too, and then I don’t even enjoy the game. But that’s one thing. What’s really maddening is that when I get home, every week all over again, like she’s doing it to spite, she’s waiting for me in the stairwell with her eyes all puffy. “Dad’s gone,” she wails, “Dad’s left us.” And me, with my head still in the soccer, it takes me a couple of minutes to understand that it’s not that her father went home, it’s that he actually dropped dead. Every week all over again the old fart has to choke on a fishbone in the middle of dinner. Die right there in my wife’s arms. “He was wheezing, and I didn’t know what to do,” she sobs, hugging me. “If you’d been here, maybe you could have done something,” she always has to add, “I mean you’re an ambulance driver, you know about these things.” And those words stab me like a knife. After that, I walk around all week with that lousy guilty feeling, every time all over again, like an idiot. I never learn.

What about “A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”?

When he wake up, the dinosaur was still there. Monterroso